Free Will and the Brain: Who Decides First?

Introduction: The Illusion of Control

We prefer to believe that we are in control. When you choose coffee over tea or decide which task to start first, the experience feels deliberate as though your conscious mind is clearly leading the decision. This sense of ownership of our actions forms the foundation of how we understand ourselves as autonomous agents.

Neuroscience complicates this intuition. What if the feeling of choosing is not the beginning of a decision but its aftereffect? This tension lies at the heart of free will and the brain: the unsettling possibility that neural processes may initiate our actions before we become consciously aware of “deciding” at all. This question has profound implications for moral responsibility, legal culpability, and our fundamental understanding of human agency.

The Libet Experiment: A Turning Point in Neuroscience

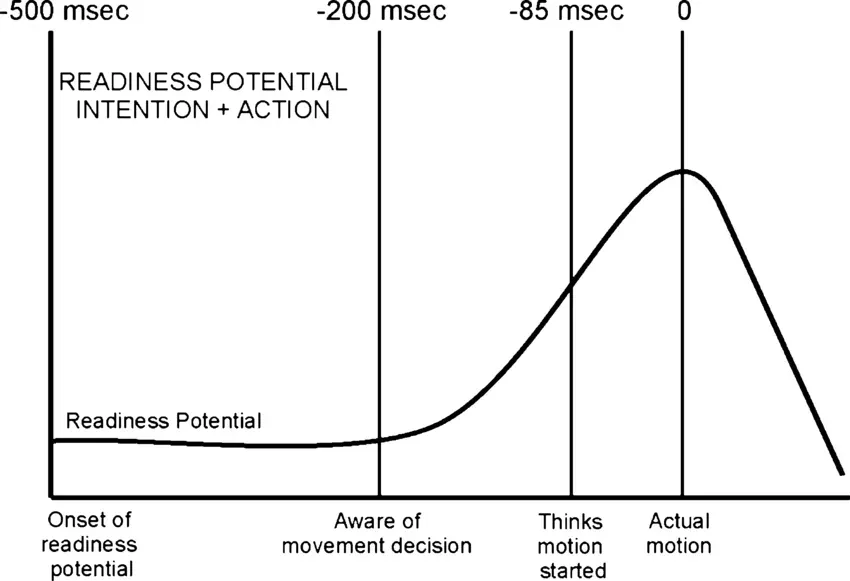

The question was cut into a sharp focus with an experiment that became famous in 1983 by Benjamin Libet. Participants were asked to perform a simple voluntary action, flexing their wrist,whenever they felt the urge to do so. While the task itself was trivial, what made the experiment groundbreaking was the methodology. Libet used electroencephalography (EEG) to measure the brain activity of the participants, which involves recording the electrical signal created by neurons firing in the brain (Libet et al., 1983).

Participants also watched a rapidly rotating clock and were instructed to note the precise moment they became aware of their intention to move. This enabled Libet to contrast three critical time points including when brain activity started, when conscious intention was formed and when actual movement took place.

The results were striking. Libet discovered a pattern of brain activity called the readiness potential (Bereitschaftspotential), which appeared approximately 550 milliseconds before the actual movement. More controversially, this neural activity preceded the reported moment of conscious intention by roughly 200 milliseconds.That is, the brain seemed to make a decision prior to the individual being conscious of the decision being made (Libet et al., 1983).

Figure 1. EEG recordings showing the readiness potential that appears before conscious intention in Libet’s classic experiment.

Image source: ResearchGate. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Such a discovery is usually understood as the negation of free will and the brain’s role in conscious decision-making. Nevertheless, such a conclusion may be premature.

Critics argue, the readiness potential may indicate an overall condition of motor preparation and not a settled decision (Schurger et al., 2012). Even Libet himself proposed the presence of conscious veto, wherein awareness can not create an action, but can suppress it prior to taking action (Libet, 1999).

Even so, free will and the brain confronts us with a challenging insight: our sense of agency may involve interpretation as much as control. Consciousness does not necessarily need to be the agent of our actions, but rather a storyteller, constructing a coherent account of decisions whose neural foundations were laid earlier.

Figure 2. Timeline showing the relationship between readiness potential, conscious intention, and actual movement.

Image source: ResearchGate. Licensed under CC BY 3.0.

In addition to Libet: Modern Neuroscience Deepens the Challenge

This issue has since been intensified in further studies to highlight our perception of free will and the brain. Neuroscientist, John-Dylan Haynes and others demonstrated that the patterns

brain activity could predict the decision made by the participants several seconds before the individuals made conscious decisions (Soon et al., 2008).

Researchers were able to read the brains of a participant in the frontopolar cortex using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of two buttons pressed by the participant up to seven seconds before the conscious decision. Seven seconds are a short time, but in the brain context, this is a considerable time. These results indicate that our perception of conscious choice can be in part thematic to what our brain is interpreting in the process of making choices. The neural processes that underlie our decisions seem to work mostly below the conscious, as consciousness seems to be an afterthought to a process that was previously in place.

Reducing responsibility through Neuroscience

The implications of free will and the brain extend beyond the laboratory and into the legal system. The present justice systems are based on the premise that people are free to make their choices and, thus, can be accountable to them.Guilt, punishment, and rehabilitation are based on this. Neuroscience, however, brings in evidence that shakes up this paradigm (Greene and Cohen, 2004).

Consider a defendant whose brain scan reveals a tumor that controls his impulses, or genetic information that he is more prone to aggressive behavior

Such examples pose a challenging question whether the neural factors that limit the behavior of an individual can be controlled or not yet how could one be answerable to the responsibility?

These situations are no longer hypothetical. In one of the most popular Italian cases, a judge cut a convicted murderer down to a smaller sentence after genetic test revealed that he had variants related to violent tendencies (Feresin, 2009). Although the decision did not justify the offense, it considered biological factors as the extenuating circumstances which indicated that the responsibility could be interpreted differently in the context of free will and the brain.

Neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky proceeds with this argument and believes that the fact that people act in a certain way due to genes, development, and neurochemistry makes moral blame uncoherent (Sapolsky, 2023).

It is based on this that punishment must yield to prevention and treatment instead of retribution. According to Sapolsky, when we have the full realization of the deterministic character of human behavior, then our whole system of moral responsibility is called into question.

This is countered by legal philosopher Stephen Morse. He says that it is not necessary to be absolutely free of causation in legal responsibility. Rather it is based on the ability of people to know what is right and wrong and to control their actions in this regard (Morse, 2011). An individual with judgment that has been impaired due to neurological injury may not pass this test; the majority of the offenders do not. This distinction preserves accountability while maintaining accountability and real constraints to control. Morse argues that the legal notion of responsibility is already compatible both with determinism and that neuroscience does not alter anything about the legal culpability.

Free Will and the Brain: A Compatibilist Middle Ground.

Philosopher Daniel Dennett provides a more balanced response to free will and the brain by postulating that the problem is brought about by an over-aspirational conception of free will.It follows that, given free will must have complete autonomy on causality, it is fundamentally incompatible with neuroscience (Dennett, 2003).

Dennett offers a more realistic explanation. On this perspective, free will is acting because of reasons, i.e., when behavior is manifested in values, character, and reflexive ability, even though those attributes may be influenced by previous causes.

Determinism does not erase agency; it explains how agency evolves.This view of compatibilism is what balances the free will with the brain by redefining free will.

According to this compatibilist view, the pre-consciousness process before consciousness does not compromise responsibility. They are not external processes working on us, but they are manifestations of who we are and are a product of experience and learning. In the long run, the act of making decisions thoughtfully literally transforms neuronal routes by neuroplasticity, which separates contemplated action and impulsive response (Pascual-Leone et al., 2005).

Responsibility, therefore, is found not in a single act of a conscious decision but in the long-run development of a self able to regulate itself and look into the future. This process is explained by neuroscience and not disproved. The association between free will and the brain turns to a process of integration and not opposition.

This is a particularly convincing opinion to me as a student studying these issues. My first reaction is something I cannot always control, but I can shape the habits, values, and environments, which will shape my future reactions. The ability to self-develop, gradual, imperfect, but a purposeful process of self-formation is a significant type of agency, even when a great part of it is carried out unconsciously.

What This Implicates in the Future.

The neuroscience of free will and the brain does not abolish responsibility, but it does demand a more informed conception of it.Punishment can hardly be justified as mere retribution when it is guided by the constraints of the neural mechanism that one cannot control.

Accountability should, however, be placed on the basis of realistic perception of human capabilities.This change advocates the preventive and rehabilitative focus over the moral discouragement. Social protection is not contingent on faith in an uncaused free will but rather on finding interventions which are consistently effective in the reduction of harmful behavior (Greene and Cohen, 2004). In neuroscience, instrumentation is provided to guide such strategies, such as seeing addiction as a disorder of the brain and creating more efficient means of controlling impulse control dysfunctions.

Simultaneously, moral humility invites free will and the brain.

Acknowledging biological limitations does not absolve the wrong, but it moderates unconsidered criticism. Explanation does not strip meaning away: love remains real despite its neurochemical basis, and ethics remains meaningful despite its neural implementation.

Being able to understand the mechanisms behind what we choose does not result in deciding those choices being any less.

With the development of neuroscience, the long-held beliefs concerning freedom and responsibility will continue to evolve. It is difficult to combine this knowledge without giving up the most important qualities in our lives: the ability to reflect, to learn and to change.

Although this capacity can be achieved by deterministic means, it could be the most significant freedom that we have. The question of free will, and the brain will continue to be one of the core aspects of philosophy, neuroscience, and law in the coming decades.

Conclusion

The problem of free will and the brain is one of the most crucial issues of the interface between neuroscience, philosophy, and ethics.

Although the experiments and the research conducted by Libet and those who follow him has shown that in most cases, the conscious awareness is significantly later than what is occurring in the brain, this does not imply that the agency is meaningless. The compatibilist approach provides a certain way out, which should both recognize the deterministic character of neural actions and the fact of human responsibility. As our understanding of free will and the brain evolves, our legal systems, moral systems, and personal concepts of what it is like to be an agent who is able to make a choice and modify things will have to evolve.

Featured Image copyright disclaimer: credit to NCCIH/NIH. Not our image.

References

Dennett, D. C. (2003). Freedom evolves. Viking Press.

Feresin, E. (2009). Lighter sentence for murderer with ‘bad genes’. Nature News.https://doi.org/10.1038/news.2009.1050

Greene, J., & Cohen, J. (2004). For the law, neuroscience changes nothing and everything. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 359(1451), 1775–1785.https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1546

Libet, B. (1999). Do we have free will? Journal of Consciousness Studies, 6(8-9), 47–57.

Libet, B., Gleason, C. A., Wright, E. W., & Pearl, D. K. (1983). Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity (readiness-potential): The unconscious initiation of a freely voluntary act. Brain, 106(3), 623–642.https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/106.3.623

Morse, S. J. (2011). Avoiding irrational neurolaw exuberance: A plea for neuromodesty. Mercer Law Review, 62(3), 837–859.

Pascual-Leone, A., Amedi, A., Fregni, F., & Merabet, L. B. (2005). The plastic human brain cortex. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 28, 377–401.https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144216

Sapolsky, R. (2023). Determined: A science of life without free will. Penguin Press.

Schurger, A., Sitt, J. D., & Dehaene, S. (2012). An accumulator model for spontaneous neural activity prior to self-initiated movement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(42), E2904–E2913.https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1210467109

Soon, C. S., Brass, M., Heinze, H.-J., & Haynes, J.-D. (2008). Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain. Nature Neuroscience, 11(5), 543–545.https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2112